Bamboo is an iconic plant that conjures images of Asia’s lush rainforests and giant pandas munching on bamboo stalks. But beyond its familiar image, bamboo has a long and rich history as a versatile natural resource utilized in construction, food, medicine, crafts, and more. One of the most intriguing facts about this fascinating plant is the extensive diversity found within the bamboo family So just how many species of bamboo exist in the world? Let’s take a closer look

Bamboos belong to the true grass family Poaceae tribe Bambuseae. There is quite a bit of disagreement over the exact number of bamboo species in existence with estimates ranging from a conservative 1,000 to over 1,600 species. Part of the difficulty in pinning down an exact number lies in the ongoing discovery and classification of new bamboo species. But most experts agree that bamboo numbers are firmly within the 1,000 to 1,500 range.

The majority of bamboo species, around 64%, are native to Southeast Asia. Another 33% originate from Latin America, while species from Africa and Oceania make up the remaining 7%. In the United States, only three truly native bamboo species are found – river cane, switch cane, and hill cane. Other bamboo species present in the US have been introduced from other parts of the world.

From a horticultural perspective, bamboos are divided into “temperate” and “tropical” types based on the climate they are adapted to. Temperate bamboo species handle colder temperatures and can survive winter lows down to 0°F (-18°C) in USDA Hardiness Zones 4 to 7. They are suitable for outdoor planting in most areas of the continental United States. Tropical bamboo species require minimal winter temperatures above 30°F (-1°C) and are restricted to USDA Zone 9 southward. They can be grown outdoors year-round only in frost-free climates like Florida and Southern California.

Another way to classify bamboos is according to their growth habit – either “clumping” or “running.” Clumping bamboos form tight, vase-shaped clumps that spread outward slowly. They are easy to contain within a given area. Running bamboos have aggressive rhizome systems that spread rapidly, making them more difficult to control. In general, clumping bamboo species dominate the tropical regions while running bamboos prevail in temperate zones. But there are exceptions in both directions.

With over 1,000 types sharing common traits but exhibiting wide variation, it’s clear that bamboo diversity is one of the many fascinating dimensions of this versatile plant. Ongoing research and exploration of bamboo’s native habitats will likely uncover even more species waiting to be discovered and documented by scientists. For now, enthusiasts can marvel at the abundance of bamboo types already identified and put to use enriching human life for thousands of years. One thing is certain – however many species there may be, bamboo will continue to captivate us with its beauty, utility, and seemingly endless variety.

Bamboo and its usage: the poor man’s timber

Bamboo has age-old connection with the material needs of rural people (Mukherjee et al. 2010). “Bamboo is one of those providential developments in nature which, like the horse, the cow, wheat, and cotton, have been indirectly responsible for man’s own evolution,” wrote Porter-field in 1933. Bamboo plays manifold role in day-to-day rural life or broadly speaking human life. It is very important for people’s cultural, artistic, industrial, agricultural, building, and household needs (McNeely 1995). The shoots and leaves of bamboo can be used to make pickles (Khatta and Katoch 1983) or traditional medicines (11). Bamboo has medicinal values too. It has multiple wide uses in ayurveda. Solvent extraction of P. pubescens and P. bambusoideae showed strong antioxidant activity (Mu et al. 2004). The mature bamboo leaves contain phenolic acids and root contains cyanogenic glycosides (Das et al. 2012). From the adult bamboo culms, high-quality charcoal is produced (Park and Kwon 1998). The umbilical cord of a newborn baby is cut with a bamboo knife in some parts of South East Asia (McNeely 1995). The knife is also used to cut the male child’s circumcision (Skeat 1900). Bamboo plays a significant role in paper and pulp industry. As reported by Sharma et al. , the national demand of bamboo was 5 million tonnes by 1987 out of which 3. 5 million tonnes were required for paper and pulp industry. B. People usually choose balcooa for building and making fiber-based mat board and panels (Ganapathy 1997), but because it is so strong, it is also used to make good paper pulp (Das et al. 2005). Bamboo is called “green gold” because of its many uses in everyday life and its economic value (Bhattacharya et al. 2009). Bamboo is widely utilized for making various musical instruments, e. g. , flutes are made from hollow bamboo (Kurz 1876). Bamboo is widely utilized for construction purposes. It can be used in many ways when building a house, like to make pillars, floors, doors and windows, room dividers, rafters, and more. (Das et al. 2008). It is also utilized for making guard wall of water bodies and river bank. Bamboo is an efficient agent for preventing soil erosion and conserving soil moisture (Christanty et al. 1996, 1997; Mailly et al. 1997; Kleinhenz and Midmore 2001).

In addition to its many direct uses by humans, bamboo is also very important in many other ways. For example, Kratter’s research shows that 25 of the 440 bird species that live in the Amazon rainforest only live in bamboo thickets. Elephants (Elephas maximus), wild cattle (Bos gaurus and B. Southeast Asian bamboos are also eaten by certain types of deer (Cervidae), primates (like macaques and leaf monkeys), pigs (Suidae), rats and mice (Muridae), porcupines (Hystricidae), and squirrels (Sciuridae). More than 15 species of birds in Asia only nest in bamboo. Many of these species are rare and endangered, and bamboo makes up a big part of their habitat (Bird Life International, 2000). The world’s second smallest bat (Tylonycteris pachypus, 3. 5 cm) nests between nodes of mature bamboo (Gigantochloa scortechinii), which it enters through holes created by beetles. These three bear species—the Asian giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca), the red panda (Ailurus fulgens), and the Himalayan black bear (Selenarctos thibetanus)—need a lot of bamboo to eat… 2003). The Red Panda (A. fulgens) is recently listed as endangered in the Red Data Book of IUCN. The Red Panda mostly eats bamboo leaves, and one of the main reasons they are going extinct in the wild is that bamboo forests are being cut down (Red Panda Network, www. redpandanetwork. org). Leaves of Sasa senanesis, S. kurilensis and S. Nipponica are a big part of what Hokkaido voles (Clethrionomys rufocanus) eat in the winter, when most other plants die.

Bamboo species have been overused and their genes are being lost, so it is important to collect and protect their germplasms (Thomas et al. 1988; Loh et al. 2000) but also to classify and characterize them (Bahadur 1979; Soderstorm and Calderon 1979; Rao and Rao 2005). It is important to characterize germplasm in order to keep it safe and use it (Stapleton and Rao 1995; Nayak et al. 2003). To keep the germplasms and protect biodiversity, it is important to look into bamboo resources and even study where they grow locally (Goyal et al. 2012); which is recorded to be limited till date.

Identification and classification is necessary for collection and conservation of germplasms (Bahadur 1979; Soderstorm and Calderon 1979). Overexploitation and genetic erosion has posed a foremost need for conservation of bamboo germplasm (Thomas et al. 1988; Loh et al. 2000). In case of any plant, the identification keys are mostly based on floral characters. Depending on the flowering cycle, the bamboos are categorized into three major groups, viz. annual flowering bamboos (Indocalamus wightianus, Ochlandra sp. ), sporadic or irregular flowering bamboos (Chimonobambusa sp. , D. hamiltonii) and gregarious flowering bamboos (B. bambos, B. tulda, D. strictus, T. spathiflora) (Das et al. 2008; Bhattacharya et al. 2006, 2009). When plants from the same seed go into reproductive phase at the same time, this is called gregarious flowering. After that, all the plants in the same cohort die (Bhattacharya et al. 2009). Incidence of flowering of woody bamboo is uncertain (Ramanayake et al. 2007; Mukherjee et al. 2010). As was already said, bamboo’s reproductive cycle is too long, lasting between 3 and 120 years (Janzen 1976), which makes it hard to tell what kind of bamboo it is by its reproductive structure (Bhattacharya et al. 2006, 2009). Consequently, the focus on identification of bamboo has shifted from reproductive to vegetative characters (Bhattacharya et al. 2006; Sharma et al. 2008).

Usually, bamboo was put into groups based on its shape. But recently, other useful taxonomic information like biochemical, anatomical, and molecular traits have been studied (Stapleton 1997) Even though bamboos have been classified so far based on their shapes, this isn’t always a good way to do it because these shapes are often affected by environmental factors. Das et al. (2007) in their work have shown that only vegetative characters are unable to distinguish closely related species. The pattern of clustering they got from using the key morphological descriptors did not fully match Gamble’s (1896) pattern of classification. People often question the accuracy of taxonomic groups that are only based on morphological traits. This is because morphological traits are controlled by a small number of genes that may not really show the whole genome (Brown-Guedira et al. 2000 cited in Das et al. 2007).

Nevertheless, DNA-based marker or molecular markers are not influenced by environment (Ram et al. 2008) and it is thus reliable for diversity analysis. Even though molecular techniques weren’t widely used for bamboo diversity analysis until the early 2000s (Loh et al. 2000). In recent years, the application of molecular technology for identification and characterization of bamboo species is predominant.

Lucina Yeasmin1Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, Faculty Centre for Integrated Rural Development and Management, School of Agriculture and Rural Development, Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University, Ramakrishna Mission Ashrama, Narendrapur, Kolkata, 700103 India Find articles by

Received 2013 Dec 13; Accepted 2014 Feb 11; Issue date 2015 Feb. © The Author(s) 2014

Open Access: This article is shared with the Creative Commons Attribution License, which lets anyone use, share, and copy it in any way, as long as the original author(s) and source are credited.

Genetic diversity is the genetic difference between and within populations of organisms. In this paper, genetic diversity refers to genetic differences between bamboo species. Bamboo is an economically important member of the grass family Poaceae, under the subfamily Bambusoideae. India has the second largest bamboo reserve in Asia after China. People often call it “poor man’s timber” because it can be used for everything from cradles to coffins. There is a lot of genetic diversity in bamboo plants all over the world. This diversity is used for both selection and plant improvement. Thus, the identification, characterization and documentation of genetic diversity of bamboo are essential for this purpose. In the past few years, many efforts have been made to use molecular markers to describe different types of bamboo so that genetic diversity can be used in the future and for conservation purposes. In this review, we talk about genetic diversity assessments of the known bamboo species that were done using DNA fingerprinting profiles, either by themselves or in combination with morphological traits by a number of different researchers. Thanks to this review, we can now start making a database of common bamboo species based on how their molecules are shaped.

Keywords: Bambusa, Biodiversity, Dendrocalamus, Molecular marker

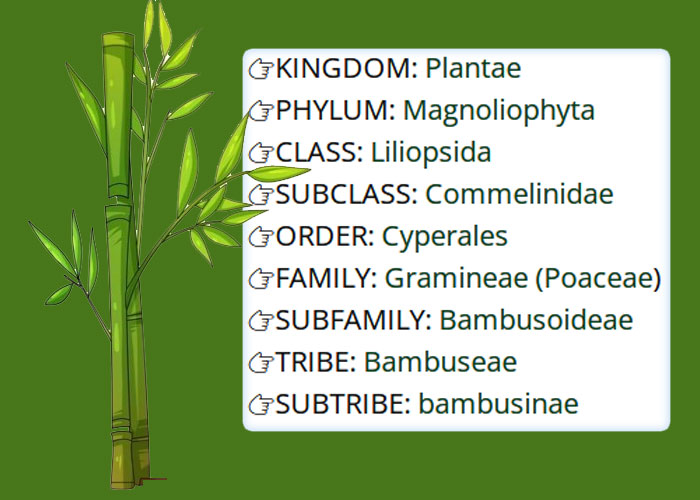

Bamboo, the fastest growing perennial, evergreen, arborescent plant is a member of the grass family (i. e. , Poaceae) and constitutes a single subfamily Bambusoideae (Kigomo 1988). The herbaceous bamboos are in the Olyreae tribe, and the woody bamboos are in the Bambuseae tribe (Ramanayake et al. 2007). The abaxial ligule is what sets the Bambuseae tribe apart from the Olyreae (Zhang and Clark 2000; Grass Phylogeny Working Group 2001). Newer classification systems put 67 genera of woody bamboos into nine subtribes, mostly based on different flower characteristics (Dransfield and Widjaja 1995; Li 1997)

Bamboo grows all over the world, from 51°N latitude in Japan (Island of Sakhalin) to 47°S latitude in South Argentina. A total number of 1,400 bamboo species are distributed worldwide. According to Behari (2006), bamboo can grow anywhere from just above sea level to 4,000 m above sea level. Bamboos cover about 14 million hectares of land, with 80 percent of that area being in Asia (Tewari 1992). The areas with the most species are in Asia and the Pacific, followed by South America. Africa has the fewest species (Bystriakova et al. 2003). It has been reported that Europe has no native bamboo species (Liese and Hamburg 1987). As of 2005, FAO says that 11,361 ha of land were used to grow bamboo, with 1,754 ha owned by private individuals. About 110 species of herbaceous bamboo grow in the Neotropics, mostly in Brazil, Paraguay, Mexico, and the West Indies. The natural bamboo forest spans about 600,000 ha and is found in Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia. It is called “Tabocais” in Brazil and “Pacales” in Peru (Filgueiras and Goncalves 2004, cited in Das et al. 2008). The Bambuseae tribe includes about 1,290 species worldwide and constitutes three major groups (Das et al. 2008). Paleotropical woody bamboo grows in Africa, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, India, southern Japan, southern China, and Oceania. It is found in tropical and subtropical areas. The Neotropical woody bamboos are distributed in Southern Mexico, Argentina, Chile and West Indies. The North Temperate Zone is home to the north temperate woody bamboos. There are also a few of them higher up in Madagascar, Africa, India, and Sri Lanka (http://www. eeob. iastate. edu/bamboo/maps. html) (Fig. 1). Bamboo can thrive in hot, humid rainforests to cold resilient forests. It can tolerate as well as can grow in extreme temperature of about −20 °C. It also can tolerate excessive precipitation ranging from 32 to 50 inch. annual rainfall (Goyal et al. 2012).

Worldwide distribution of bamboo. a Neotropical woody bamboos, b north temperate woody bamboos, c paleotropical woody bamboos, and d herbaceous bamboos (Source: http://www.eeob.iastate.edu/bamboo/maps.html)

After China, India has the most genetic resources for bamboo, making it the second richest country in this area (Bystriakova et al. 2003). Several reports have been found regarding the species richness of bamboo in India. Reports on the number of bamboo species range from 102 (Ohrnberger 2002) to 136 (Sharma 1980). Bahadur and Jain (1983) listed about 113 species. In India, 9. 57 million ha which is about 12. 8 % of the total forest area of the country is covered by bamboo plantation (Sharma 1980). As opined by many scientists, the distribution of bamboo is greatly influenced by human interventions (Boontawee 1988). However, Gamble (1896) has earlier reported that the distribution of bamboo in India is related to rainfall. In a different report from 1980, Varmah and Bahadur found that different species of bamboo grow best in different types of soil in India. Arundinaria and Thamnocalamus grow in the alpine region, while Phyllostachys and these two genera grow in the temperate region. In the subtropical region, Arundinaria, Bambusa, and Dendrocalamus grow. In the tropical moist region, Bambusa, Dendrocalamus, Melocanna, Ochlandra, and Oxytenanthera can grow. In the dry tropical region, Dendrocalamus and Bambusa are more common (Ahmed 1996) (Fig. 2).

Dendrocalamus and Bambusa are the two most common species of bamboo in India. They grow in subtropical, tropical moist, and tropical dry climate zones. aBambusa balcooa, bBambusa bambos, cBambusa tulda, dDendrocalamus asper, eDendrocalamus hamiltonii, fDendrocalamus strictus (Source: Authors).

Bamboo species identification with Natalia Reategui: Bambusa balcooa

FAQ

How many species of bamboo exist?

What is the most valuable bamboo to grow?

How many species of bamboo are known to mankind?

Does all bamboo take 5 years to grow?

How many types of bamboo are there?

Since 1981 the American Bamboo Society (ABS) has compiled an annual Source List of bamboo plants and products. The List includes more than 490 kinds (species, subspecies, varieties, and cultivars) of bamboo available in the US and Canada, and many bamboo-related products. The ABS produces the Source List as a public service.

How many types of bamboo grow in America?

In America, there are only three species of bamboo that grow naturally. These three species once covered nearly five million acres of land in America, until settlers began to tear down this “Cane Break” for farming lands. Any other species of bamboo that grow in North America are generally those that have been transplanted from other places.

Is bamboo a genus or a subfamily?

Botanists and plant scientists define bamboo as a subfamily, Bambusoideae, within the grass family, Poaceae. And before we get to the genus or the species, which typically follow after the family, the bamboo subfamily is divided into three tribes.

Where does bamboo grow naturally?

Of the many kinds of species of bamboo out there, 64% of the varieties of bamboo growing naturally do so within the Southeast Asia regions. 33% of the species grow naturally in Latin America, and the last 7%, give or take a few species, grow in the Africa and Oceana regions of the world.

How many species of running bamboo are there?

Today there are three species of running bamboo, all native to North America, which officially belong to this genus. In other words, the great majority of authors recognize only those three species as true Arundinarias. In former times, however, this genus had as many as 400 species.

Are bamboo trees native to America?

The Americas also host a diverse array of bamboo species, with notable concentrations in Central and South America. The towering Guadua angustifolia, a prominent species in the region, is revered for its strength and durability, making it a popular choice for construction and furniture.