Cherry tree enthusiasts look forward to it each spring: a mass explosion of light pink blossoms. Cherry tree diseases aren’t very exciting for people who love the flowers and the sweet fruit they produce. If you think your cherry tree might be sick, we’ve put together a list of the seven most common diseases, their symptoms, causes, and how to treat them.

Signs of disease can be frightening. When these pathogens attack a whole orchard of cherry trees, they kill all the pretty flowers and juicy fruit. But when cherry tree growers take the right precautions, they make their trees less likely to get diseases and increase the chances of a strong bloom and a tasty harvest.

Cherry Trees Affected: Black knot is a common disease of ornamental cherry trees. It also affects most types of Prunus, including edible and native types. East Asian cherry, North Japanese hill cherry, and Prunus maackii (Manchurian cherry or Amur chokecherry) are all types of cherry trees that are resistant to black knots.

Signs: Black knot (Dibotryon morbosum) looks like hard, black knots or swellings that can be 1 to 6 inches long on the tree. These knots appear in various areas around the tree and enlarge when the disease is left untreated.

Velvety, olive-green fungal growth may cover the knots. Diseased twigs often bend due to knot overgrowth. Infected branches may wilt, not grow leaves, and can eventually kill the entire tree.

Causes: Through spring and summer, mature knots produce spores. The rain and wind then carry the black knot fungus spores to susceptible plants.

The spores can germinate and infect new plants in six hours at the optimal temperature and wet conditions. By fall, light brown swellings appear on infected twigs. The following spring, the growing knots develop the olive-green fungal growth. As the year progresses into summer and fall, the knots become hard, rough, and black.

Treatment: Prune 3-4 inches below the knot during the dormant season. Sterilize all pruning equipment. Burn or bury all infected material; otherwise, it may still be able to infect healthy trees. Remove cherry trees that have a severe infection.

The Wisconsin Horticulture Division of Extension does not suggest using fungicides because the treatment is pricey and most likely will not work.

Risk: Black knot can limit the production of cherries and ruin the appeal of ornamental cherry trees.

Problems with Cherry Trees: The Kwanzan flowering cherry tree has brown rot because it is one of the most likely to get it. It is also a common weeping cherry tree disease. Many stone fruits, including peach and plum trees, are also affected.

Symptoms: Brown rot (Monilinia fructicola) symptoms first occur as the browning of blossoms and the death of twigs. Leaves on the infected twigs turn brown and collapse but remain attached to the tree.

Powdery masses of brown-gray spores may be visible on infected fruits, flowers, or twigs when the weather is right and it’s wet.

If the infected flowers don’t fall off, the disease can move from the flower to the next-door twig. Twigs then develop cankers, which further produce fungal spores of the disease.

Brown rot thrives best in warm, wet conditions, causing infection to occur in as little as three hours. Insects can act as spreading agents for this fungal cherry disease.

Treatment: Once brown rot infects your cherries, there are no curable treatments for the fruit. Clean the pruning shears and cut off any parts of the tree that are hurt 4 to 6 inches below the dead tissue that has sunk into the ground. Burn or bury the pruned materials to prevent the infection from spreading.

Thinning your fruit trees encourages airflow, allowing for a drier environment to deter the fungus. If brown rot is unmanageable and continues to infect your trees, consider using fungicides.

Cherry blossom trees are known for their beautiful pink and white blooms that only last for a short period in spring. However it can be heartbreaking if your beloved cherry tree starts declining and dying. Don’t give up hope yet! With some TLC and proper care you may be able to nurse your cherry tree back to health.

Signs Your Cherry Tree is Dying

- Sparse foliage, leafless branches

- Smaller leaves than usual

- Leaves turning yellow or brown and dropping early

- Twig/branch dieback

- Lack of new growth

- No flowers or fruits

- Oozing lesions, cankers on bark and branches

- Presence of fungi (mushrooms, mold) at base of tree

Common Reasons for Cherry Tree Decline

Pests Aphids borers mites, caterpillars and other pests can damage leaves, twigs and trunk.

Diseases: Fungal diseases like black knot, brown rot, cytospora canker can infect the tree. Viral infections like necrotic ringspot can also occur.

Environmental factors Excessive drought overwatering, extreme cold late spring frosts can stress the tree. Storm damage or lightning strikes can instantaneously damage the tree.

Poor drainage: Waterlogging from poor drainage causes root rot and stresses the tree.

Mechanical injury: Damage from lawn mowers, string trimmers and other equipment can wound the trunk and roots.

Old age: Cherry trees only live around 30 years on average. Dieback of branches and trunk are signs of senescence.

Root damage: Trenching, soil compaction, construction activities can damage fragile surface roots.

How to Save a Dying Cherry Tree

Step 1 – Inspect for signs of pests or disease

Closely check all parts of the tree and surrounding soil for any visible signs of infestation – chewed leaves, sawdust-like frass, egg masses, fungal growths, discolored sap/ooze. Send samples to a plant diagnostic lab if needed.

Step 2 – Rule out non-biotic factors

Ensure the tree is getting adequate sunlight, watch for signs of drought stress, check if lawn care activities are injuring the tree, assess if extreme weather events preceded the decline. Identify and mitigate any non-living factors.

Step 3 – Improve growing conditions

- Prune dead branches, disinfect tools after every cut

- Aerate compacted soil, add organic compost

- Apply 2-4 inches of organic mulch avoiding direct contact with trunk

- Deep root feed the tree with liquid fertilizer injections

- Water deeply and slowly within the dripline during drought

Step 4 – Use appropriate pest and disease treatments

- Apply horticultural oil or insecticidal soap sprays to control soft-bodied pests like aphids

- Remove bagworm bags, caterpillar nests by hand

- Apply neem oil or fungicides to prevent spread of certain fungal diseases

- Remove and destroy severely infected/infested parts via pruning

Step 5 – Consider rejuvenation pruning

If more than 50% of the canopy is dead, try rejuvenation pruning in early spring. This stimulates new growth from the trunk and main scaffold branches.

Step 6 – Fertilize the tree in spring

Apply a balanced 10-10-10 fertilizer or compost/manure tea around the dripline. This provides important nutrients for recovery. Avoid excess nitrogen.

Step 7 – Monitor tree vigilantly

Watch for recurrence of symptoms and immediately treat any new pest/disease outbreaks. Providing vigilant care in the initial years after decline is key.

When to Remove a Dying Cherry Tree

If more than 80% of the canopy is dead and no new leaves emerge after rejuvenation pruning, the tree may be too far gone. At this stage, removal may be the best option before the tree becomes a safety hazard. Talk to an arborist about risks associated with retaining a severely declining tree. If infected with a major disease like black knot, removal may be required to prevent spread.

Signs of Recovery

- Increased leaf size and density

- New shoots emerging from branches and trunk

- Flowers and fruits returning

- Cankers drying out and healing over

- No more branch dieback or defoliation

With prompt diagnosis and proper care of underlying issues, you can still turn around a declining cherry tree. But be prepared that it may take 2 to 3 growing seasons before your cherry tree regains its former vigor. Patience and persistence are key!

Cherry Leaf Spot

Cherry Trees Affected: Cherry leaf spot (Blumeriella jaapii) attacks tart, sweet, and English Morello cherries.

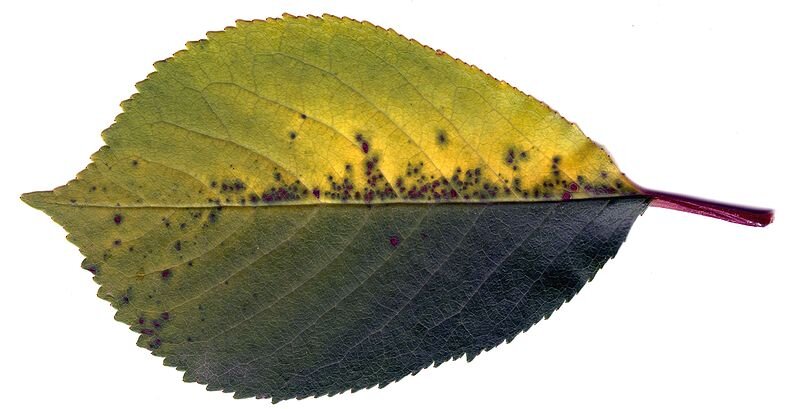

Symptoms: This disease affects the cherry tree leaves, and may appear on leaf petioles and fruit pedicels. Small purple spots develop on the upper side of the leaf. These spots will enlarge to approximately 1/4-inch in diameter and turn a reddish-brown color.

The spots may dry out and fall off after six to eight weeks, leaving small holes in the leaf. Sometimes older infected leaves may turn golden yellow before falling off. Cherry leaves infected with cherry leaf spot may fall prematurely. It’s not the same as leaf scorch, which looks like cherry tree leaves turning brown and curling instead of falling off.

Causes: This fungal disease overwinters in dead cherry leaves on the ground. In early spring, apothecia (fruiting bodies) develop on the leaves and produce spores. Rainfall spreads these spores to healthy leaves where the spores germinate and penetrate the leaf.

The small purple spots begin to appear on the leaf after infection. Once these spots have developed, their undersides create more fungal spores (conidia), which appear as whitish-pink underleaf lesions. Rain then spreads the conidia to other healthy cherry trees and creates new infections.

Treatment: Gather and destroy all fallen leaves to prevent the fungus from overwintering. Taking off the leaves is a good way to grow cherry trees in your own yard, but it’s not always the best idea for large cherry orchards. When you plant your cherry tree, make sure it gets direct sunlight and plenty of air flow (pruning can help with this).

In commercial orchards, fungicide is the best method to control the disease. The Ohio State University Extension recommends Bulletin 506 for commercial growers and Bulletin 780 for backyard cherry tree growers.

Season: The purple spots appear on cherry leaves between the end of May and the beginning of June.

Risk: A cherry tree with a severe infection may defoliate by mid-summer. Early and repeated defoliation may cause unripe fruit with poor taste. Cherry trees are more likely to get hurt in the winter, lose fruit, have weak buds, and even die. This can happen to fruit-bearing branches called fruit spurs.

Cytospora canker (Leucostoma kunze), which affects cherry trees, is one of the worst diseases for both sweet and sour cherries.

Symptoms: Cherry tree branches develop dark, depressed cankers that cause the tree branch to wilt. An amber-colored gum may appear at the edge of the canker. The canker will eventually girdle the limb and you’ll notice parts of the cherry tree dying.

Causes: Black pycnidia, spore-producing structures, appear on the canker. These black pycnidia will turn white over time. In humid conditions, spore masses expel from the pycnidia. Rain and wind carry the spores to infect any bark wound. These wounds may result from sunburn, old cankers, or wood-boring insects.

This disease cannot attack healthy, undamaged bark. A cherry tree’s susceptibility to Cytospora canker increases when it’s stressed from drought, nutrient deficiency (i.e. low potassium), overcropping, and ring nematodes.

Treatment: There is no chemical control for Cytospora canker. Control infection by limiting tree stress. This is the best time to prune your infected cherry tree because the cankers and dieback limbs are easier to see.

Season: Cytospora canker thrives in the summer when temperatures are above 90 degrees. Dead limbs girdled by cankers appear in mid to late summer.

Risk: Formed cankers will kill parts of your cherry tree.

Cherry Trees Affected: Sweet and sour cherry trees are the most susceptible to powdery mildew (Podosphaera clandestina). Powdery mildew is also a common weeping cherry tree problem.

Symptoms: Light powdery patches appear on young cherry leaves. Older leaves are less likely to have powdery patches as they may have resistance to powdery mildew. Infected leaves may distort, twist, or grow pale. A white fungus may develop at the stem end of the cherry.

Causes: In the fall, small structures (chasmothecia) containing ascospores lie dormant in leaves or where tree limbs come together (crotches). During rainfall or irrigation, these structures release the ascospores. The wind carries the ascospores to infect young leaves.

By fall, the fungal infection enters its overwintering stage in the chasmothecia to repeat the cycle next season. This disease favors humid conditions and temperatures between 70 to 80 degrees.

Treatment: Avoid early irrigation as this may cause premature powdery mildew infections to rise. The ground should still be moist in the spring, and unnecessary watering may cause powdery mildew to begin infection. According to Washington State University, a two-week delay in irrigation can delay the disease with no negative impact on the fruit.

Pruning your cherry tree will encourage airflow and leaf dryness. Keep in mind that most fungicides are only meant to stop the disease from happening; they do not cure it.

Season: Practice preventive management methods throughout the full fungal growing seasons in late summer and early fall.

Risk: Mid-and-late-season sweet cherries are commonly affected. Powdery mildew may ruin your cherry fruit with a white fungal growth on the cherry surface.

Cherry Trees Affected: Necrotic ringspot attacks sweet and sour cherries.

Symptoms: Symptoms include yellowing and browning of cherry leaves. Leaves develop holes, giving them a shothole appearance. Leaves may drop in early summer, and the cherry fruit may deform or mature later than usual.

The spread of this disease is much slower in sweet cherries than in sour cherries. Enations or raised projections will form on the underside of leaves, giving a thick and stiff appearance.

Causes: The virus, Prunus necrotic ringspot virus (PNRSV), spreads through pollen, seed, and wood grafting. Wind and pollinators can spread infected pollen throughout an entire orchard.

Treatment: Remove symptomatic trees to prevent spread to other cherry trees.

Risk: Necrotic ringspot may stunt your tree’s growth and kill its twigs, buds, and foliage. PNRSV can cause fruit losses of up to 15% in sweet cherries and up to 100% in peaches.

Cherry Trees Affected: Sweet and sour cherries are commonly affected by silver leaf.

Symptoms: The first symptom of silver leaf (Chondrostereum purpureum) is a silver sheen on the affected leaves. The precise number of leaves affected will vary from tree to tree. The silvery leaves may develop brown, dead patches, and leaf symptoms may not appear year after year.

If they appear one year, they may not reappear the next. Do not mistake the lack of symptoms for a full recovery. Branches with symptomatic leaves may have a dark stain running underneath them. In diseased trees, you may notice a white fungus on the cherry tree bark with noticeable purple-brown conks.

Causes: The conks are reproductive structures of the disease-causing fungus. Fall rains let the fungus out of the conks, and it then spreads to trees with open wounds and infects them. The fungus then lives in the water-conducting tissue of branches (xylem). Its presence in the xylem is what causes the dark stain.

The fungus releases a toxin, which then travels to the leaves and causes a silvery appearance. The epidermis (the surface layer) separating from the rest of the leaf blade causes the metallic sheen. This separation impacts the reflection of light. As the wood decays, the disease begins to develop the fungus-producing conks on the wood.

Treatment: Prune branches showing any leaf symptoms or signs of conks. Prune branches at least 4 inches below where staining and conks are visible. Mark your diseased trees. At that point, you will know to pay close attention to that tree the next year if the symptoms don’t come back.

Because the fungus stops water from moving through the branches, give the sick trees enough water—about 10 gallons for every inch of the tree’s diameter. No fungicides are available to treat this disease.

Season: Prune infected trees during dry winter periods when temperatures are below 32 degrees. Pruning at this time will help prevent the spread of silver leaf. If pruning in the growing season, ensure you are doing it in dry conditions.

Risk: Silver leaf will cause a slow decline in your cherry tree’s health and fruit yield.

What Are The Symptoms Of Cherry Tree Fungus?

It can vary based on the fungus. Black knots or swellings, silver leaves, light powdery spots, depressed cankers, and leaves falling off are all signs that something is wrong.

Ethanol or isopropyl alcohol is great for cleaning pruning tools because the blades can be wiped or dipped into the disinfectant without having to soak for a long time.

What Mysterious Thing KILLED my Cherry Tree?!? | Something ATE My Fruit Tree Roots!

How do you save a dying cherry blossom tree?

Prune affected branches, promote air circulation, and ensure the tree is adequately mulched to create a healthier environment, reducing the risk of infestations. Saving a dying cherry blossom tree requires a comprehensive approach that addresses various factors contributing to its decline.

How do you care for a cherry blossom tree?

Deep watering, especially during dry periods, is essential. Conduct a soil test to determine its pH and nutrient levels. Cherry blossom trees thrive in slightly acidic to neutral soil. Adjusting the soil’s pH and providing appropriate fertilization can address nutrient deficiencies. Trim dead or diseased branches to encourage new growth.

Can a dying cherry blossom tree be revived?

You should identify the problems of a dying cherry blossom tree before it can be revived. It is advisable to cut off the dead branches and focus on revitalizing the remaining parts of the tree. If you are unsure whether they are dead, wait until the following spring before pruning any branches that don’t have new growth.

Can you save a dying Cherry Tree?

Cherry trees that are dying can be saved if you find the primary issue and employ the right solution. Typically, it takes several weeks or months for a cherry tree to completely die, depending on the issue. To see if your cherry tree is still alive, prune a small branch and see if there’s any green inside. 1. Over or Under-Watering

- The Ultimate Guide to Growing Strawberries in Raised Beds - August 8, 2025

- No-Dig Garden Beds: The Easiest Way to Grow a Beautiful Garden - August 6, 2025

- How to Protect and Preserve Wood for Raised Garden Beds - August 6, 2025